Noise Damage: My Life as a Rock ‘n’ Roll Underdog by James Kennedy, Lightning Books Ltd., 2020

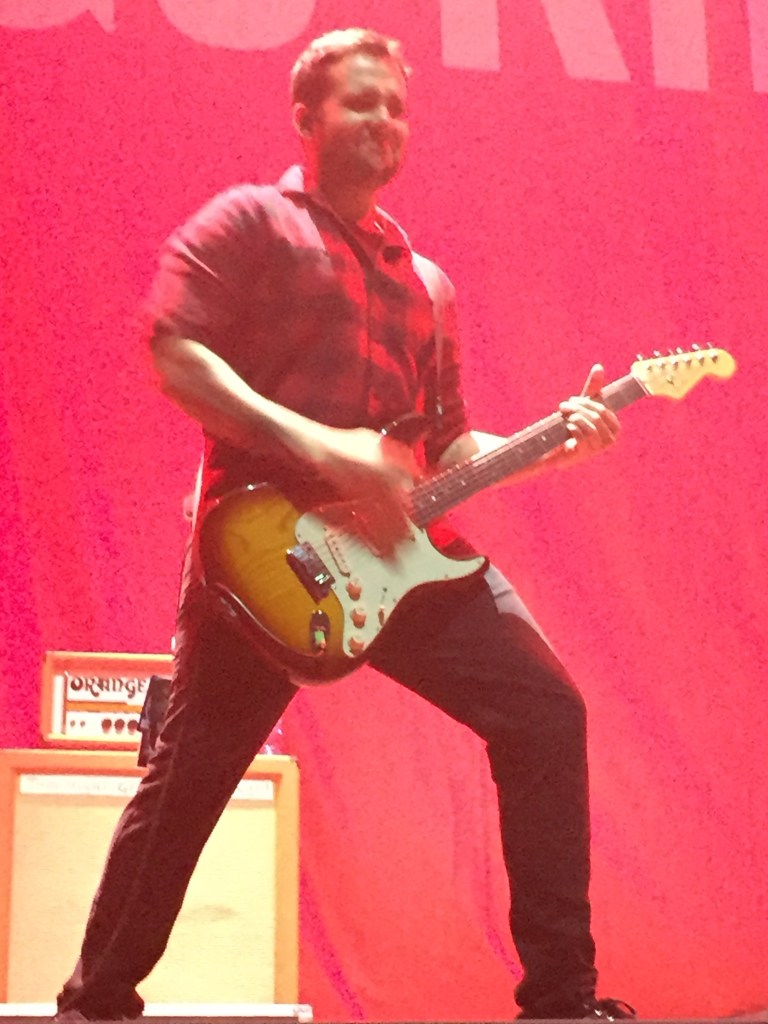

Noise Damage is a great read. It’s written in a breezy, honest style that makes you feel like you’re sitting in a pub with Kennedy as he regales you with his story. But it also feels like you’re peering into a hidden world. If you’ve ever been crushed in the pit at a rock concert and wondered what it’s like to be up there, to get on the bus every day and do it again and again, if you’ve wondered how they got there and why —Noise Damage will tell you.

Noise Damage is the story of a guy from backwater Wales who just wants to be a rock star. But the book is also a memoir, a soul-searching telling of what it means to claim your real calling. In Kennedy’s case, that calling is making music.

Born in 1980, Kennedy grew up in a working-class family in south Wales. Leaving Cardiff not long after Kennedy was born, the family moved first to a gritty, urban area, and then to a village “in the middle of bloody nowhere.” On his ninth birthday, Kennedy’s dad gave him a little Spanish guitar (that he later learned his father had “nicked from somewhere’) and showed him a few things on it. “I played that damn riff over and over (and over),” Kennedy writes, “maybe a thousand times, and the fact that I could actually do something with this thing made me feel like I’d just discovered a buried superpower.” After a few “lessons” from a one-legged, Hendrix-worshipping local guy called Sid, Kennedy knew he could only be a guitarist.

But the path to rock glory would not be easy. The road took a serious turn a year later when doctors found tumors in both Kennedy’s ears. Surgeries left him with only sixty percent of his hearing and ferocious tinnitus.

Kennedy was a “frustrating paradox”, struggling through school despite being a voracious reader well-versed in literature, history, and politics; he celebrated the end of high school by setting fire to his uniform and books. But high school was a means to an end: getting into college to study music.

Through sheer will power, Kennedy made it to college, where he encountered music theory for the first time—and snagged an opportunity to work in a real music studio.

Once Kennedy found his way around the studio, he seized a further opportunity—to make an album, “the album, that threw all of the things I loved into one giant, ambitious, uncommercial, multi-genre melting pot of seething, unpredictable musical indulgence [with] an angry dose of politics and … filthy noise and pounding drums.” This was Made in China, his first CD (later remade as Kyshera’s 2nd album in 2012).

With his no-holds-barred approach and absolute belief that he could do whatever he set his mind to, coupled with the digital technology that was changing the music industry, Kennedy made the entire album himself, writing and singing every song (despite having never written or sung a song), playing every instrument—digitally or otherwise—recording, engineering. It took two years of putting in every spare moment, often working through the night, until it was done. Then Kennedy even handled his own promotion, mailing CDs to all the music magazines.

This is where Kennedy’s story really takes off. Awash with rave reviews, every interviewer and industry big-wig wanted to know: “When are you next performing in London?” Kennedy had to get a band together. After plastering most of Wales with recruitment flyers (no social media, no internet back in the day), his band, Kyshera, began to take shape.

Kyshera’s run was a roller coaster ride. From crazed, screaming drummers and the exhilaration of the band’s first gig to the hard reality of the music industry’s crash and burn; from their first festival—before a crowd of bikers, where frontman Kennedy managed to fall and slash his face open in the middle of the set, spraying blood everywhere—to endless weekends playing covers to make money just to put gas in the bus to get to the next gig. A trip to Toronto for a major festival proved to be the gig from hell with a full-throttle adrenaline rush, sufficient to lure them back a second time—all against a backdrop of trying to hold on to the day job and have a personal life.

Peppered with British-isms, you might wish you had a Duolingo app for British slang. And if the “bad” words were left out, Noise Damage would be a much shorter read—I warned you it’s honest writing! And don’t read this book to get an understanding of the music industry or how to break into it; Noise Damage is not that.

Noise Damage is about coming of age, about truly embracing one’s calling no matter what it costs. And these days, when kids are forced to decide their direction early on, Noise Damage stands as a truthful telling of what it means to pursue your dream in a real world that can be brutal, unkind, and downright mean. Noise Damage is also an expression of irrepressible spirit, persistence despite significant odds against success, and the saving grace that is music.

Next time you get to a concert early to claim your spot at the rail, and you’re confronted with a band—the opener—that’s not the one you came to see, give them a listen anyway. As Kennedy says at the end of Noise Damage: “P.S. Please support artists. It’s harder than it looks.”

I first came across James Kennedy’s music through a tweet from July 2020, promoting the first single from his most recent album, Make Anger Great Again, “The Power”.

For something completely different, try Kennedy’s latest release, “Insomnia”.

You can also find on Spotify the audio book of Noise Damage, read by James Kennedy.

James Kennedy is also on SoundCloud & Bandcamp.